Join Kathy in pondering by visiting the following articles:

How Living In India Impacted a Book About War

Lessons from A Duck

This I Believe

Courageous Conversations

You’ve Got to Do What You’ve Got to Do

How Living In India Impacted a Book About War

© Kathy Beckwith 2016

Published in KODAI, A Class News Magazine for Alumni and Friends of Kodaikanal International School, Tamil Nadu, India, 2016/2017.

Lessons from A Duck

© Kathy Beckwith, Winter 2015

We returned from a conference to find heavy rains had left so much flooding at home. Wayne and I, and son Kip, spotted a distressed Mallard duck in the field across the road from our house. The rains had created a small pond where the male was gently paddling back and forth, keeping vigil over his mate, which had obviously recently died and was bloated, floating in the pond nearby him. I had learned about the Malabar Gray Hornbill when we were in India – how they mate for life – and heard that in devotion to its mate, the male brings food to the nesting female and young. But I didn’t know that a common duck would feel that kind of bonding and devotion, even staying near its mate at the time of death, as this one was doing. Watching him, I soon realized that he was no longer “common” to me, but quite amazing.

The duck was still circling around its dead mate the next morning when I went walking, so I stopped and talked to it through the fence, then went back to the house for my camera and took some photos. I thought our kids would want to know what I had learned about the Mallard duck’s habits and loyalty. Somebody said one of the kids was out duck hunting that day, but, well, the others might want to know, and probably he would too. Before I walked on, I sang to the duck, and I hoped it somehow understood that it must leave, take care of itself, and get food.

I didn’t want to find it there on the third morning when I went walking. But not knowing what I would see, I took a small bag of Cherrios with me … just in case the duck was still there. Sadly, it was. I could hardly imagine how it was surviving. I walked around the fence at the end of the field, and doubled back to the pond, where I tossed Cherrios out onto the water, some close enough for the duck to scoop them up, I was sure. But it seemed distracted, uninterested. Or perhaps it was just entirely focused on its mate. About then Kip came jogging along.

“Uh, Mom,” he said. “I think we’ve got a couple of plastic ducks here.”

So it was…

I guess there’s always something to learn, and be surprised by!

This I Believe (and continue to ponder…)

© Kathy Beckwith 2011 (written for Oregon Mediation Association’s call for essays: This I Believe)

I believe in wonder and in wondering – amazement and curiosity, astonishment and inquisitiveness. I believe that wonder, with its dual meanings, when put into action, will solve most of the world’s problems. Probably all of the world’s problems. And it can start with kids and mediation.

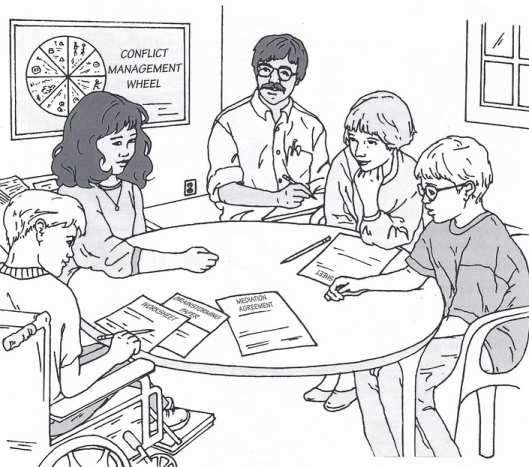

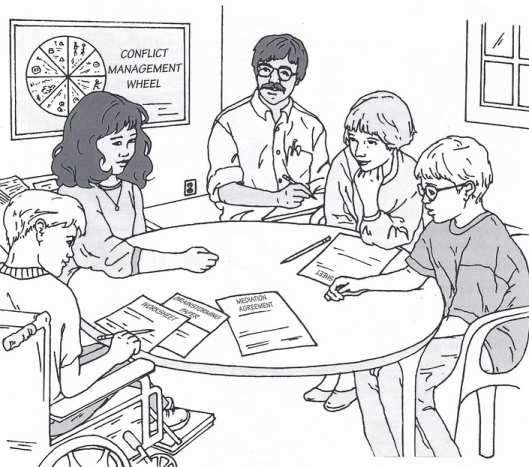

First, the wonder. I’ve worked with peer mediation in schools for nineteen years. I am amazed, but no longer astonished, at what I see kids do when we give them the tools. I attended a conference at about year four. The presenter said mediation was too advanced a skill for the elementary school child. I didn’t know that when I began training nine-year-olds and found they could do it. They had the same empathy, desire to help, creativity, and commitment I saw in the seventeen-year-olds. Parties came to the table with sour faces and locked-in positions, and left grinning and feeling like heroes. After coaching hundreds of mediations, I know without a doubt that kids make it work.

First, the wonder. I’ve worked with peer mediation in schools for nineteen years. I am amazed, but no longer astonished, at what I see kids do when we give them the tools. I attended a conference at about year four. The presenter said mediation was too advanced a skill for the elementary school child. I didn’t know that when I began training nine-year-olds and found they could do it. They had the same empathy, desire to help, creativity, and commitment I saw in the seventeen-year-olds. Parties came to the table with sour faces and locked-in positions, and left grinning and feeling like heroes. After coaching hundreds of mediations, I know without a doubt that kids make it work.

Wondering? Sparking curiosity is at the heart of mediation: What’s the deal with that person? Why don’t they get it? What’s their story? Could there be another solution? Students look at another’s reality, tell their own story, work hard, and discover options they never knew existed. I’ve seen racial issues melt as bilingual mediators put their language skills to work, sifted through what really happened, and helped the parties find their one word solution. I’ve seen a young woman stand in her own strength against sexual harassment with the power of a signed agreement in her hand. I’ve seen crazy, complicated solutions devised that my brain would never have stormed in a lifetime, created by youth excited to carry them out. I’ve watched mediators wonder at struggles their classmates deal with outside of school, and give support. They “bounce back” (paraphrase) at home, and mediate in the park. After being to mediation twice, a boy prone to fighting was overheard threatening a classmate: “You better knock it off, man, or I’m gunna take you to mediation!”

Yet I return to wondering: Why don’t we give every school child this opportunity? Why don’t educators, mediators, and students team up and make it happen? I believe kids learn problem-solving by doing. They deserve to experience an alternative to the violence of their nation’s way of dealing with conflict. In turn, they will be global networkers, sharing the sanity and power of humane, just problem-solving, instead of violence.

We found a bird’s nest under our apple tree, woven entirely of mule hair. Utterly beautiful engineering! Martin Luther said we’d die of wonder if we just understood a grain of wheat. Walt Whitman said sextillions would stagger over the miracle of a mouse. If only we could see the miracle in a mouse! Or an apple tree. Or a mule’s tail. If only people could see the miracle of kids mediating, they would stagger in wonder! And the world would change.

This I Believe, Part 2: Courageous Conversations Are Needed by Mediators (and non-mediators!)

© Kathy Beckwith, 2011 (written October 4, 2011, and still so needed today)

October 4, 2011

I believe courageous conversations about our nation’s habit of violence are desperately needed. Last weekend’s news (Sept. 30 – Oct. 1) reported the U.S. had sold 55 bunker buster bombs to Israel, quietly, when we said we’re working for peace in the Middle East. It reported a CIA-U.S. military drone attack assassination of a suspected terrorist and another man in Yemen, both U.S. citizens. We have “declared” a war on terror – of undetermined duration, location, methods, and goals – so, being at war, we are free to throw a rope over the nearest tree and string ‘m up without being bothered by the rule of law, constitutional or human rights, or international criminal justice.We are currently conducting U.S.-initiated wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. We are involved in war in Libya “to prevent civilian casualties,” yet one of our first strikes was on Gadhafi’s son’s home where his father was staying at the time, killing the son and three grandchildren. Quite a way to protect civilians.

Mediators, who know deeply the work of resolving conflicts and facilitating the search for creative and just solutions, have a unique opportunity to spark courage in conversation by questioning: How can the work we do apply to international conflict? What is the background of this situation? What needs are behind the positions? What options are possible rather than the violence of war, secrecy, assassination? How can mediators tell the story of what works? How can we challenge the acceptance of institutionalized violence which we’d never accept personally or in our mediation work?

I believe training in mediation gives us more than a good work or rewarding volunteerism. It gives us knowledge and experience in the effectiveness of purposeful, reasonable, humane, and just problem-solving. To say that stops at our borders short-changes America and the world. To say that others, trained in violence, know more about problem-solving than we, is short-sighted. To hear that people in Government have the inside story and must be trusted, should make us wonder why we don’t have that inside story. Once our nation’s habit of violence makes us less secure and less safe, we have every right to raise a ruckus. Or at least a courageous conversation! I believe we are at that point.

Our current wars, assassinations, and global militarism are modeling something very destructive – reliance on violence to accomplish goals. There is little question that we choose violence as a primary tool of international dealings. When we have more people employed in military bands than work in the entire foreign service of our country, things are out of whack. I work in school conflict resolution. I believe the United States Government undermines the work I do with youth. When our nation trains young people to become killers, when Congress gives up its responsibility to declare war, when military spending skyrockets and schools close, when kids have more access to recruiters at school than to mediation, we’re undermined.

Let the courageous conversations begin!

You’ve Got to Do What You’ve Got to Do

© Kathy Beckwith 2013

I hate making a fool of myself. It feels bad. For quite a while. I find myself re-running the incident mentally, muttering, “How dumb,” or “Good grief, why did I do that?” I heard a sermon once on learning how to say, “Oh well.” Easier said than done. I know I shouldn’t be so hard on myself. That’s why I love what my kids did for me…

My daughter and I were invited to take part in the planting of a Peace Pole in a neighboring town. Our part was a role play, and telling a true story about a spinning top, which I took out of my pocket and held up for the crowd to see. But before the program had ended, conflict broke out between two other presenters. Peace Poles don’t innoculate us against conflict, it appears. And this one was surprisingly heated, tense, and not stopping. I stepped out of the crowd and walked toward them. I had no idea what I was going to do. Suddenly I felt my hand reach into my pocket for the top. I had an inkling that I might be about to make a fool of myself, and at that very moment, I hoped my daughter would not be ashamed of me.

We talked about it the next day, my daughter and I, and my son. How the top had somehow shifted things momentarily, and the two presenters changed course. But then I confessed to the thoughts that had flitted across my mind as I had stepped out of the crowd. My daughter said, “I didn’t know what you were going to do. But I was saying, ‘Go for it, Mom. Somebody has to do something.'” I loved her matter of fact acceptance. Then my son added, “Mom, don’t ever worry about us being embarrassed because of something you do. You do what you need to do, and we’ll be okay.” Then he smiled and added, “Course, I might say, ‘Nope, that’s not my mom!'”

I loved having their okay to make a fool of myself if need be. I don’t know why it matters, but somehow they’ve made it easier for me to step out of the crowd, even when I have no idea what I’m doing. I suppose you’ve just got to do what you’ve got to do, even if you’re not sure you’ll be able to say, “Oh well.”

First, the

First, the